The Corridor Project

Our vision is a San Francisco Bay Area Wildlife Corridor. UWRP notes that as population, development, and sea level increases, it is of utmost importance that the wildlife thoroughfares are identified and preserved. To help maintain California’s natural genetic diversity, UWRP’s goal is to map, protect, and enhance the corridors that wildlife use to travel from one region to another. We will partner with other wildlife organizations and government agencies to research and link the wildlife corridors to create a San Francisco Bay Area Wildlife Corridor to ensure the protection of the region’s rich natural heritage.

Beginning with the South Bay

After years of researching the behavior of Gray Foxes in Palo Alto, some observations have left us doubting the genetic health of the foxes; including floppy ears, incest, and overpopulation. We began to hypothesize what factors led to these conditions. Could it be that human development has isolated the foxes, preventing them from leaving the baylands? UWRP set out to answer this question by broadening their search of the gray fox to near by San Frasiquito Creek and the surrounding baylands. To our surprise, most places we looked, we found signs of these ashy canines.

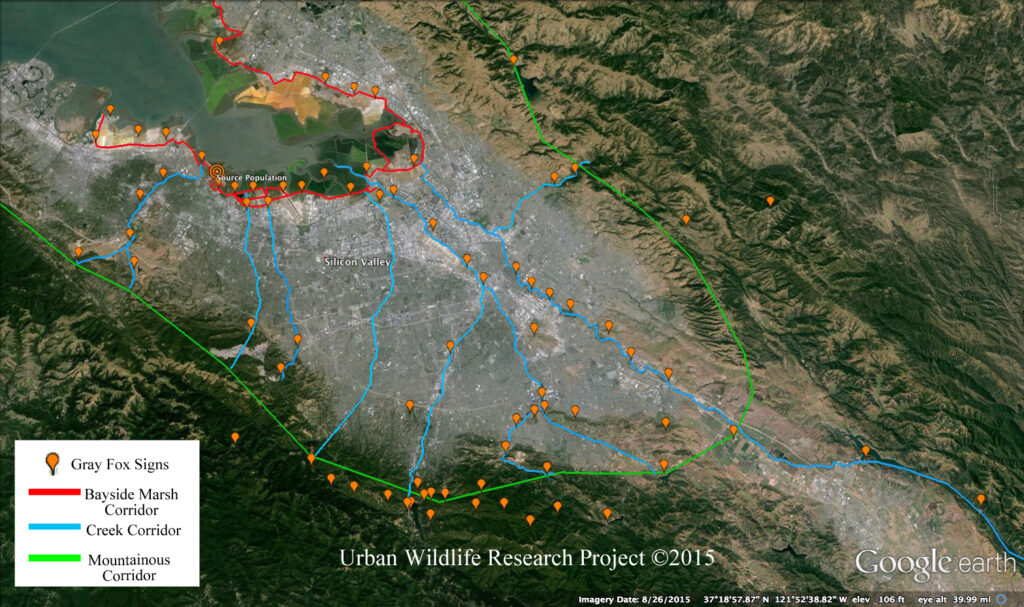

We began mapping our sightings and widening our search to all of Silicon Valley and the mountains surrounding. Anyone can contribute to our project by sending us their Gray Fox sightings and photos. The Gray fox has been found on the Campuses of Google, Facebook, and Stanford. As well as in Downtown San Jose, at the Sharks Stadium and running down 15th street through the Naglee Park neighborhood. These foxes, we’ve dubbed Urban Gray Foxes, are showing signs of adaptation to the urban landscape, following the footsteps of the raccoon, skunk, and opossum.

After creating the fox map we came up with a new question, how are these different populations of foxes related to one another? To answer that we’ve designed a DNA project that will commence late 2016. We will revisit the locations on our fox sightings map and collect fresh scat for analysis by a university lab. We hope to be able to find evidence of genetic linkage between the Gray Foxes in the Santa Cruz and Diablo mountains to the foxes living around the bay. From this data we can hope to discover which creeks are a viable corridor or path from mountains to bay. We will also do a complete DNA marker analysis on the scat to better understand the Gray Fox’s diet in the many different kinds of habitat around Silicon Valley.

When looking at the fox sightings map, UWRP connected the dots to find the corridors, or paths the animals take to navigate the urban landscape. They have identified Coyote Creek, Guadalupe River, Los Gatos Creek, and San Francisquito Creek as possible paths from the in the mountains to the bay. When looking at the map you see the big picture, but out in the field when searching for the exact path the animals take, we find their route can be complex and dangerous. Through backyards, under culverts, over barbed wire, and across busy freeways. We hope by identifying these problem areas we can make the path safer for wildlife and humans; by correcting fencing to channel wildlife under culverts and constructing or improving wildlife crossings.

Habitat loss, fragmentation, and isolation are major factors in the decline of our wildlife populations worldwide. Citizens and organizations can help this project by volunteering, donating funds for research, and becoming a member of the SF Bay Area Corridor Coalition.

Coyote Creek and Coyote Valley

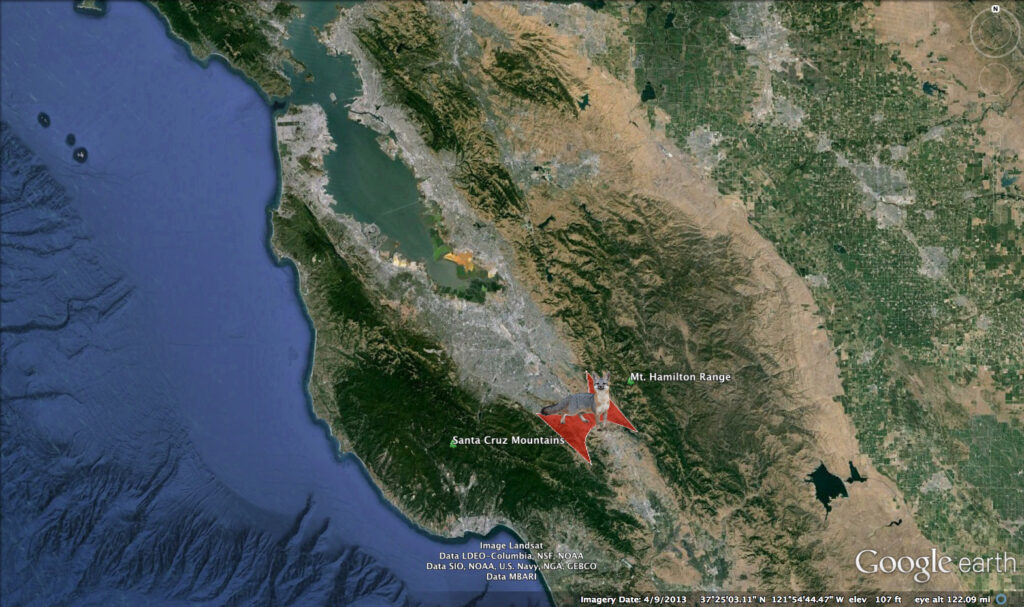

Coyote Creek flows north from San Antonio Valley, connecting with many creeks along the way through San Jose and out to the Bay. One crucial connection point for wildlife along this creek, is a place known as Coyote Valley. This area is the closest distance between Silicon Valley’s two mountain ranges, The Diablo(or Hamilton) and Santa Cruz Ranges. Coyote Valley is just 0.4 miles at the narrowest end and 2 miles at the widest, with Highway 101 bisecting the land. The valley’s land use is mostly agricultural and contains some of San Jose’s last agricultural land from the days of The Valley of the Heart’s Delight.

This route is how the valley’s wildlife connects with the rest of California and the continent. Without this linkage our wildlife may be stuck in the Santa Cruz Mountains, with little place to go. Isolation can lead to poor genetic health, disease, population decline, and even extirpation(or local extinction) of certain species.

Wildlife researchers at De Anza College and Pathways for Wildlife have done some amazing research tracking wildlife across Hwy 101 and the valley floor. They found that some wildlife uses about 30 crossing structures to find safe ways of crossing the Valley and freeway; such as underpasses, overpasses, culverts and waterways. There are talks of a Wildlife Crossing over Hwy 101 to provide a car free path for wildlife through Coyote Valley. Below is some preliminary research UWRP has done in the area north of Coyote valley which still provides linkage between mountain ranges.

In this map, Coyote Creek flows under the Hwy 101 and 85 interchange. UWRP followed the foot prints of animals from the Diablo Mountains, safely under 101 and 85 and on to the Santa Cruz Mountains side. We documented the tracks of Bobcats, Coyote, Gray Fox, Deer, Boar, Rabbits, Ground Squirrels, Harvest Mice, Quail, lizards, and frogs passing safely under the freeway. Even spiders, butterflies, and newts need these corridors as a safe link around our man made obstacles. Despite the underpass, wildlife still gets hit along the motorway in this location, due to inadequate fencing. Our goal is to partner with Caltrans and land owners to improve fencing to minimize animal vs automobile incidents and direct wildlife to safe passage.

Coyote Valley is under constant threat of development. Open flat land is hard to come by in San Jose and fetches a pretty penny. Coyote Valley could very well end up another piece of the concrete web of Silicon Valley tech campuses and industry, but, there is a major effort to preserve the land. Join the effort to preserve Coyote Valley, find out more at: https://www.facebook.com/ILoveCoyoteValley/

The Guadalupe River Corridor-The Santa Cruz Mountains to the San Francisco Bay

From the mountain springs of Mt. Humunhum and Loma Prieta, through Downtown San Jose, and out to the San Francisco Bay; the Guadalupe River may be the most intact creek corridor in the region. But for larger animals like the bobcat and mountain lion it may be too over developed to allow passage from mountains to bay. Downtown sky scrappers are built, sometimes with little or no buffer to the bank of the river. The sandy, rocky river bottom is replaced with concrete blocks to prevent erosion and speed up the water’s journey to the bay to prevent flooding. These areas with poor habitat conditions and little to no plant cover provide little opportunity for wildlife movement. Yet the Coyote and both Red and Gray Foxes have been spotted in the Guadalupe River Park and Gardens in the middle of Downtown San Jose.

Riparian Setback; The natural vegetated space between a stream or body of water and human development. Many local governments in the nation have mandated Riparian Setbacks, for example, Contra Costa County does not allow building within 150 feet from a stream. Very few cities and developments along the creeks and rivers of Silicon Valley take Riparian Corridors into consideration. With out proper setbacks our bayside terrestrial and aquatic wildlife may be left cut off from the rest of the state.

Fish Need Corridors Too

Our anadromous, endangered listed, fishy friends like the Chinook Salmon, Steelhead Trout, and Pacific Lamprey use these creek corridors as well. Improper Riparian Setbacks and concrete river banks, among other things, negatively impacts them too. These fish need cool uninterrupted flows with a proper river bottom. Their journey through the Guadalupe River often stops before the finned ones reach the cool mountain streams; at the dams: Calero, Almaden, Guadalupe, and Vasona. The dams not only cut off the flow of fish upstream to better spawning grounds, they stop cobble stones from rolling down stream to create good fish spawning habitat. Our lower watersheds eventually become bogged with mud and silt. The concrete river bottoms in the more urban reaches of the streams are troubled with unnatural and high temperatures. Proper Riparian Setbacks, good cobble, and improving fishes access to mountain streams are what the declining fish populations are signaling for.