Disease and the Gray FoThe Dynamics of the Gray Fox’s Diet

by William C. Leikam

President, CEO & Co-founder, Urban Wildlife Research Project

I stood behind trail camera number two out on the concrete overflow channel at about 5:30 AM. Dawn shrouded the baylands. The two foxes that live in this region were some 30 or so feet away. Male Laimos (Means long neck in Greek) trotted toward me. His mate Big Eyes, much more skittish than he, lagged behind, stopped, crouched and defecated there in the channel. I had been watching for that moment for nearly two years, ever since these two gray foxes had come into the area and claimed it. Knowing which specific gray fox defecated would tell me a good deal about that individual gray fox’s health and what it ate.

That afternoon I examined her scat. I found that she had been dining on a variety of plants that contain seeds. There were the remains of elder berries, rose hips, Italian Buckthorn and other seeds that I did not recognize. There was no fur as one might expect from a carnivore. Although gray foxes are omnivores, it looked to me that Big Eyes was in her summer diet of fruits, berries, and vegetation. Most gray fox transition from being predominantly a carnivore to being predominantly a “vegetarian” during the summer months when fruits and berries are available. This shift in diet is a common trait of the gray fox in Central California. By early fall they will eat a mix of rodents and whatever vegetation remains. By December they will begin to transition back to eating meat once again so that by the time their pups arrive in April, they have returned to eating meat on a regular basis.

Except for Rachel N. Larson’s research in Food Habits of Coyotes, Gray Foxes, and Bobcats in a Coastal Southern California Urban Landscape, there is no in-depth look at why this dietary transition takes place. For our purposes here I need to extend it by making a few assumptions. One, there’s likely to be a good reason for this shift in their diet other than by December there’s no longer fruit available in our research area. According to personal sources, even in areas where there is fruit available, they transition to a meat-based diet.

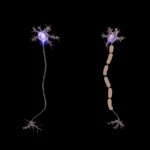

So, where does this take us? Drawing on research that I did on the structure of the human brain several decades ago, I learned a few facts about neurological development that may be relevant here. During the in-utero development of a human fetus the nervous system becomes sheathed with myelin. It “… is a lipid-rich substance that surrounds nerve cell axons to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be likened to an electrical wire with insulating material around it.” Wikipedia

Section III

Gray Fox, Baylands Goals

Within the permit that allows the Urban Wildlife Research Project to conduct its study of the behavior of the gray fox at the Palo Alto Baylands Nature Preserve, the objectives covered area:

- Monitoring of urban gray fox Denning sites in Palo Alto Baylands.

This is being accomplished during the period when the gray foxes use a den site. It is one of the prime locations for gathering most of the behavioral data of the litter and for adults alike.

- Assessment of status and population trends of Baylands urban gray foxes

Since January 2019 a pair of resident gray foxes have claimed territory at the Palo Alto Baylands Nature Preserve.

- Identification of habitat features that promote the presence of urban gray foxes

After considering this and talking with people who know how to restore habitats, we need to assess what kinds of plants, including the Alkaline Salt Bush, would grow best along the edge of the saltwater channel and alongside the marsh. We need to grow a permanent habitat that contains the corridors and plant it as soon as possible. We’ll keep an eye on this as this is a critical link between the southern region of the Baylands and the northern region.

- Assessment of reproductive success and identification of factors that promote successful reproduction

Open up the pinch-point along Matadero Creek by developing thickets that link one area to another, instead of the present “islands”.

- Identification and assessment of possible dispersal travel routes.

Presently there can only be guesses as to dispersal travel routes. We intend to make this important question much more concrete when we attain our collaring/take/capture permit from the Department of Fish & Wildlife.

For the myelin to properly develop and sheath the nerve, a diet of protein is required. (An interesting aside, the research shows that girls develop this sheath in-utero more quickly than do boys and thus girls are born developmentally more mature than their brothers.) The myelination of the nerve cell continues even after birth. If there is little to no protein in the diet the sheath cannot properly develop. The unsheathed axon continues to function but it transmits information at a much slower rate than a myelinated axon. Mental retardation can be the result.

For the myelin to properly develop and sheath the nerve, a diet of protein is required. (An interesting aside, the research shows that girls develop this sheath in-utero more quickly than do boys and thus girls are born developmentally more mature than their brothers.) The myelination of the nerve cell continues even after birth. If there is little to no protein in the diet the sheath cannot properly develop. The unsheathed axon continues to function but it transmits information at a much slower rate than a myelinated axon. Mental retardation can be the result.